7

Ladakh and Alchi

When is a Hare Not a Hare?

Nothing can prepare you for the sheer beauty of the paintings at Alchi. It is like walking into the Sistine chapel for the first time, only the chapel is a Buddhist temple, it is relatively dark, much smaller and you have to stoop as you enter. It is also a much more intimate experience. You come face to face with the paintings in the darkness and you discover the quality of the artwork picture by picture. Alchi is much earlier, the temple walls were painted about 1200AD, at least three hundred years before the Sistine chapel. You also need a torch, so it is more like looking at cave paintings.

The artists at Alchi are thought to be from Kashmir because of the dress of the people depicted and scenes from Kashmir at a time when Kashmir was a great centre of Buddhist art and learning. This was the tail end of a rich Buddhist culture which had its roots in Gandhara and lasted for over a thousand years. It was only terminated by repeated Muslim invasions and interventions. The fact that Alchi and its paintings survive at all is something of a miracle.

The trade routes from the north, from Yarkand, Khotan and Kashgar which connected Central Asia and China to Kashmir and North India ran over the Karakoram over three major passes then right through Ladakh along the corridor provided by the River Indus close to Alchi. The Indus rushes past, cold and fresh from Tibet but the monastery cannot be seen from the old road which may account for its survival.

River Indus at Alchi. Photo © Carol Trewin

Alchi is a small but ancient monastic complex in a rural setting amidst fields of wheat and barley surrounded by poplars and apricot trees. Alchi is also that rare thing a special monastery where translations, transmission and advanced teaching took place: a place of retreat and initiation, and a powerhouse of knowledge and Buddhist philosophy. Such sites are not just monasteries – in Tibetan they are known as chos’khor11 which literally means ‘Dharma wheel’ ie places where the wheel of the Buddha’s teaching always turns. The wheel of doctrine. Not to be confused with the mani wheels which also turn and spread blessings.

Other important chos’khor in the Tibetan world were at Tabo monastery in Spiti, as well as Tsaparang in Guge, Western Tibet. The white temple in Tsaparang has a Four Hares motif on the ceiling.12 There are two important temples Lhakhang Marpo (Red temple) and the Lhakhang Karpo (White temple). There is another famous monastery not far away called Tholing. As it happened, the ancient Kingdom of Ladakh was often in conflict with Guge in Western Tibet. Slowly over the years Ladakh shrank in size and Guge was absorbed into Tibet, but at the time of the Alchi paintings, Ladakh was a force to be reckoned with and rivalled Central Tibet and Lhasa. Gold panned from river deposits and alluvial goldfields provided ready cash to pay for artists and the building of temples.

White Temple, Tsaparang, Guge, Western Tibet (Ngari Prefecture).

So in Ladakh there is to this day an unbroken chain of monasteries and learning that connects them right back through Alchi to Kashmir, which was at that time Buddhist. Kashmir was itself connected back to the world of Gandhara, Afghanistan and Swat. But after these monasteries in Kashmir were destroyed or became redundant, these later smaller teaching monasteries, set deep in the mountains of Ladakh, became very important and were like jewels in a chain leading towards Tibet. It was through Ladakh that the Buddhist teachings finally reached Tibet for the second time. So the importance of these temples cannot be overstated.

Harvest, Alchi, Leh district of Jammu and Kashmir, India Photo: Carol Trewin

Today Alchi is a quiet backwater forty miles west of Leh and is under the supervision of Likir Monastery.13 In the old trading days, which only ceased in 1947, it was eight days from Leh for a caravan of yaks and ponies to reach Kargil and Alchi is about midway. Alchi must have always been an important site as there are also many stone carved petroglyphs of men hunting ibex which are several thousand years old; these can be seen on large boulders dotted along the river bank, as well as graffiti from early Tibetan soldiers.

Ibex Carvings on the banks of the River Indus. Photo: Carol Trewin

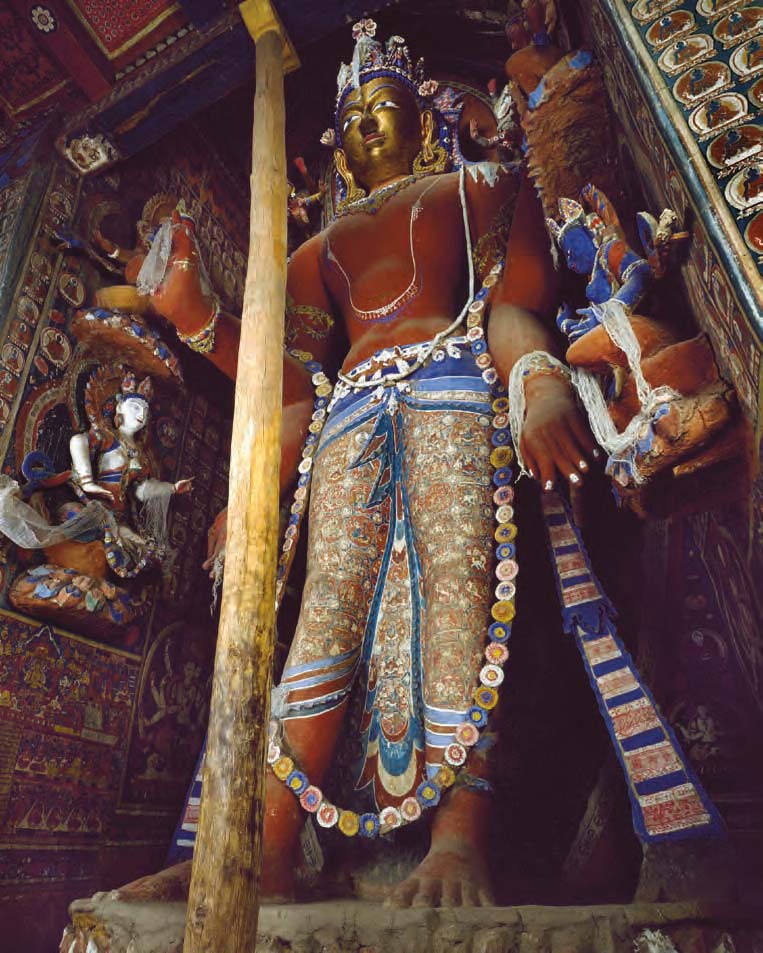

Alchi has three major shrines: the Dukhang (Assembly hall), the Sum-tsek and the Temple of Manjushri as well as many interesting chortens. The Three Hares symbol is to be found in the Sumtsek or three-tiered temple, painted time and time again onto the robes or dhoti of the central figure, the Maitreya, the Buddha to come.

As to the date of the Sumtsek temple and the painting there is some debate. According to local tradition the Alchi monastery complex was built by the great translator and artist Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo14 who lived between 958 and 1055. Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo was sent by the King of Zangskar down to Kashmir to obtain teachings and was at the forefront of the Second Diffusion which brought Buddhism back into Tibet. There are many legends surrounding his life. He is said to have built several important monasteries in Western Tibet, including Tabo in Spiti, Tholing in Guge as well as Nyarma and Sumda in Ladakh. In Ladakh any early temple is often attributed to Lotsawa Richen Zangpo! But the paintings at Alchi, acccording to modern scholars, who have studied accompanying texts and dedications, may well date from a century later: 11th–12th centuries.15

At Alchi the outside façade of the Sumtsek temple is wooden and is leaning outwards at a rather alarming angle. On the façade there are many ornate carvings and some of the small pillars on the upper storey have Greek style capitals ‘Ionian’ carved in wood and triangular ‘A’ frames with carved figures in the niches. To gain entrance to the temple one has to go through a very low doorway and it is very dark indeed.

The Sumtsek temple entrance, showing intricate wood carving in Kashmiri style, c1200AD. Photo: Carol Trewin

Only after a while do your eyes become accustomed to the light inside the temple. The main central figure of Maitreya is about fourteen feet high and the lower half is covered in a dhoti or loincloth, which is elaborately painted. It is this dhoti which is of great interest. The loincloth is made from stucco that has been expertly painted to make it look as if it is fabric. This is where the Three Hares occur in small rectangular lozenges, though there is some debate as to whether they are actually hares at all.

Statue of Maitreya, Sumtsek temple, Alchi c1200AD © Jaroslav Poncar

The dhoti on the Maitreya has painted on it a series of scenes from the Buddha’s life, past and present. It is very colourful indeed. The extensive work that academic and art historians have put into recording the paintings in Alchi is truly magnificent as are the photographs of Jaroslav Poncar.16 These scenes from the Buddha’s life are set within roundels, rather like cameo shots, and between the scenes, as if holding the whole fabric together in a framework are the images of three ‘hares’ with conjoined ears which are racing round and round in a clockwise direction. There are over fifty sets of these ‘hares’ which amounts to over 150 hares in all, holding the whole ‘textile’ together.

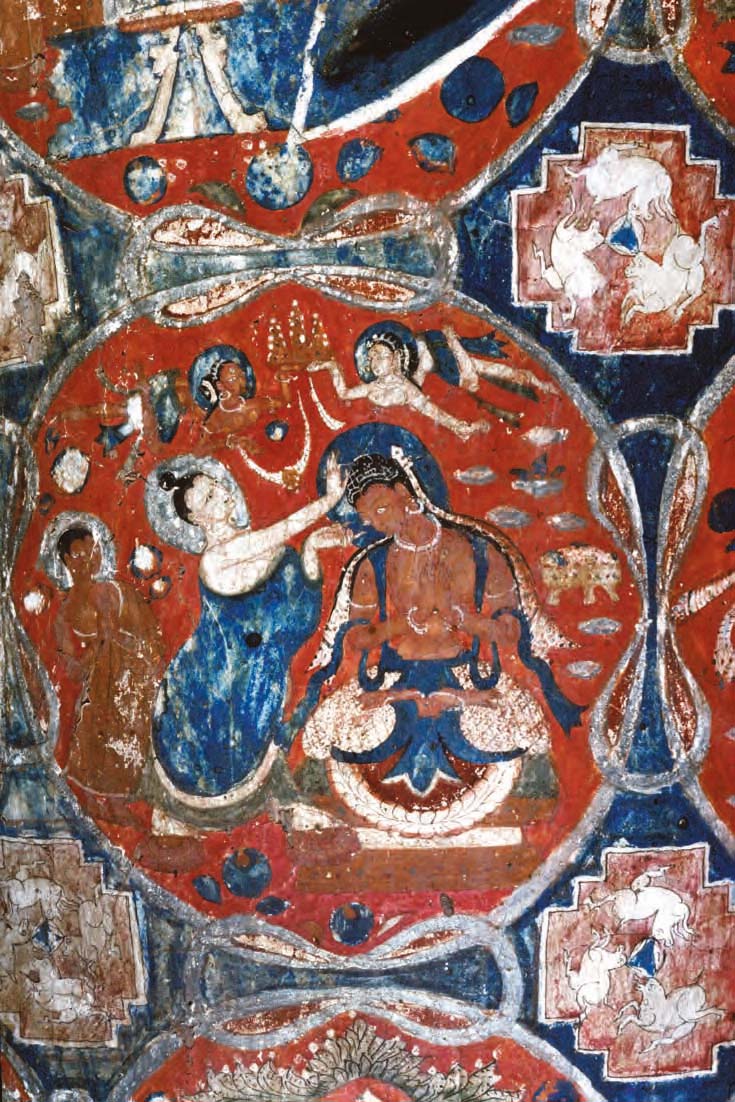

Detail of Maitreya’s dhoti showing scenes of the Buddha’s life. Sumtsek temple, Alchi © Jaroslav Poncar

These Alchi ‘Hares’ are all linked with what looks like a prototype vajra which means both ‘thunder bolt’ and ‘diamond’ in Sanskrit and is called dorje in Tibetan. They may just be loops used to draw the design together in figure of eight, but early Buddhists, like early Christians, were fond of secret or obscure symbolism. If it looks like a vajra it may well be a vajra.

The thunderbolt is a Tibetan ritual weapon used in puja or evocations of certain deities. The vajra may also apply to the teaching which is called Vajrayana, or Tantric Buddhism which was very popular at the time Alchi monastery was founded. And then you get onto some very interesting ground indeed.17

Detail of Three hares and a figure of eight pattern that is like a primitive vajra, Sumtsek temple, Alchi © Jaroslav Poncar

In their book published in 1977 detailing the temples at Alchi, the Buddhist scholars David Snellgrove and Tadeusz Skorupski from the School of Oriental and Asiatic Studies were the first to document the temples in Alchi.18 Sadly they do not mention the three ‘hares’. It is however a significant part of the dhoti and occurs over fifty times. A later book by Ravi Kumar 1988 shows illustrations of the three hares but mentions them as leaping ‘bulls’, which he thinks might be linked to ceilings in Ajanta. However they do not really look like bulls either… yaks possibly!

Another respected academic Professor Roger Goepper from Cologne is also not sure that they are in fact hares, but he makes the point that some of the other animals portrayed at Alchi are very lifelike indeed, for example elephants, horses and deer.19 In Tibetan art some animals like the Tibetan snow lion have mythical status, in other words they live in our minds and work their power there.

Dr. Christian Luczanits in his article about the Sumtsek in Orientations 1999 calls them deer, and they do seem to have hooves, which might prove his argument, but they are not very slender and deer-like. So are they by any chance mythical or transcendental hares, or do they represent something totally different? Have the hares transformed into deer?

Detail of the Three Hares, Sumtsek temple, Alchi © Jaroslav Poncar

What is perplexing is that the figures at Dunhuang which are several centuries earlier, are very clearly hares, slender and athletic; and the later the cave paintings become, the chubbier the hares grow. The Three Hares in Dunhuang are often in prime position, in pride of place within a lotus in the centre of the ceiling. Are they depicting enlightenment, or form and emptiness in the very centre? Or are they showing the ceaseless round of teaching. And are they male or female? Do they symbolise fertility and the moon?

At the royal fortress of Basgo fifteen miles down the road back towards Leh, three centuries later than Alchi, the four hares have paws which definitely makes them hares, or at least rabbits. But by then the painters were indigenous Ladakhis who knew their game. Why would anyone suddenly opt for deer in Alchi? The deer park at Sarnath? The Buddha’s first sermon?

The answer may lie in local conditions. The local Ladakhi hare is the indigenous Tibetan woolly hare which is found on the Tibetan plateau. It is chunkier than its counter-part in Europe, has a longer tail, and is definitely woollier. It has to survive in minus 40ºC in winter. So there is a possibility that the hares as portrayed in Alchi are mythical creatures, transcendental hares; or drawn as if someone has described them, although they have not seen them for real themselves. Even in medieval Europe early animal paintings were often drawn like this, from informed imagination.

But there is another explanation to the hare/deer/rabbit mystery, as Godfrey Vigne points out in his book Travels in Kashmir Ladakh and Iskardu (1842). He is amazed, as a keen sportsman, to find that there are no hares in Kashmir at all, despite the good terrain, which he finds perplexing. As it is too cold for Indian Hares and there is not enough cover for Tibetan Hares, it is possible that Kashmiri artists may not have even seen a Tibetan hare. So for the moment we shall call them Hares.20

That there are no hares in Kashmir is echoed by Sir Walter Roper Lawrence in his 1895 book The Valley of Kashmir. There is a theory that all the irrigation channels in Kashmir made it impossible for the hare to run around unimpeded, so they legged it to more open ground. There are plenty of hares in Persia, Afghanistan and Central Asia. Eagles and hawks were trained to hunt for hares. Even Hittites hunted with eagles.

So it is just possible that the Kashmiri artists had not seen a hare close to, or they may have been working from hares depicted on woven textiles.

The Three Hare symbol in the Sumtsek temple in Alchi is no mere ornament but an integral part of the design. The vajra is a ritual object to symbolize both the properties of a diamond (indestructibility) and a thunderbolt (irresistible force). The thunderbolt can also imply the ‘thunderbolt’ experience of Buddhist enlightenment or bodhi: the sudden awakening which is part of the Zen experience.21

The Three Hares can symbolise the Three Jewels: Gonchuk sum (gsang ba gsum): Buddha, Dharma and Sangha; that is, the Buddha, the teaching and the community of monks, which is used when taking Refuge, or starting out on the path. Or in this instance, at a more advanced monastic setting, it may be more specific as in the Three Jewels related to the Buddha’s teaching. There are the three vajras: the enlightened body, speech and mind of a Buddha. This would fit in perfectly with the idea of enfolding and embracing scenes from the Buddha’s life and their relationship to the Maitreya, the Buddha to come. The Three Vajras are also known as the Three Secrets, Three Mysteries, Three Seats, Three Doors and Three Gateways. or simply ‘the three secrets of the noble ones’ ie lus, body, gsung voice/speech and thugs mind. So there you have it. The three ‘hares’ may well be deer but still have three conjoined ears and still charge round and round on the dhoti of the Buddha to come. Or they may just be imaginary hares or deer, or even yaks!.22

The main point is that the Three Hares symbol (or Three Deer symbol) is painted in very important positions in the Sumtsek temple and in the Great Stupa. We can only wonder at their true meaning. But the fact that they occur at Alchi, in Tsaparang, Spiti and at Basgo is important. They do not seem to occur in later settings when the Tibetan wall paintings became more formal and stylistic. Alchi is still holding onto some of its secrets. It is an extraordinarily important site. Professor Snellgrove describes it as ‘a fantastic chance survival from the past, and truly one of the wonders of the Buddhist world’.