10

Buddhist Conversations About Hares in Ladakh

The last time I visited Alchi was in 2003. This was for a conference organised by The International Association of Ladakh Studies which was held in Choglamsar near Leh and was attended by scholars from many different countries, and many local Ladakhi scholars which was wonderful. After the conference I made a trip with Dr John Crook to Alchi and Basgo.25 The main aim at Alchi was to make recordings for a future BBC programme about the Three Hares. Dr John Crook was an old friend of mine, a well-known scholar and Buddhist teacher with years of experience in Ladakh. He was also a pioneer ethologist at Bristol University.

With his help we were able to interview some important Ladakhis who enabled us to understand the Buddhist context of the Three Hares. These learned and delightful Ladakhis were Dr Jamyang Gyaltsen,26 Nawang Tsering Shakspo,27 and lastly the well known and highly respected Buddhist scholar, translator and historian Tashi Rabgyas28 whom we met in Leh. I had known Tashi since 1976. One other visiting academic at the conference who was also very helpful was Dr Christian Luczanits from the Institute for South Asian, Tibetan and Buddhist Studies in Vienna.29

The cultural context in Ladakh is very important, stretching back in time for over a thousand years. Nowhere else in the world, it seems, is there any direct knowledge at all about the Three Hares symbol, not even in China. It is as if to understand the Three Hares/Four Hares symbol in Ladakh, one has to understand it from within, not from the outside: one has to think like a Tibetan Buddhist. And this will by its very nature also give important clues to the Chinese context at Dunhuang. One has to think like a nangpa, an insider, which means a Buddhist, that is from within the teaching and from within the culture.

Knowledge from local villagers was also important. Nawang Tsering Shakspo for instance said that he had recently given a lift to an old man, near Sabu and he had asked him about hares. ‘He said “Yes. Yes.” He said he knows all about hares, there are many hares in my village; they are beautiful, we sometimes address them, calling them rigung chang-chub-tsempa which means “hare bodhisattva”.’

Why bodhisattva?

‘These animals they are very peaceful animal and if somebody chases them, they just stay there closing their eyes and they are meditating. So this animal must be very interesting or intelligent or very auspicious. He said “Yes. Yes they are an auspicious animal, therefore people don’t kill it”.’ that was his impression. Of course the hares were bodhisattvas. Why else were they be depicted on the robes of the Maitreya?

In Ladakh is the hare a sacred animal?

“Yes. Bodhisattva means being kind hearted. Some animals have special place like fish, deer and hare. By birth they were very holy. Deer don’t harm any animal. I place deer and hare higher than fish. Very auspicious animal. Deer and hare most sacred animals.”

So in Ladakh and the Tibetan Buddhist world the hare is a very potent symbol, a symbol of compassion forever going round and round.

Dr Jamyang Geltsen, from the school of Buddhist studies in Leh, took a more philosophical and traditional view and said that the Three Hares represented ‘The Three Jewels, the Famous Three Jewels of Buddhism: Buddha, Dharma, Sangha, and if the deer were deer, then that points to Sarnath and the first sermon. Four Hares? The Four Noble Truths. The four noble deer.’ It was obvious…

So it could be that the three and four hares in Ladakh and Dunhuang both refer to the earliest Buddhist sermons and to texts in the deer park – Noble Hares, Bodhisattva Hares, Three Jewelled Hares.

Dr John Crook was also as perplexed as I was by the hares that looked like deer. “They have hooves but then they change in time at Basgo back to hares.” A connection to the Buddha’s first sermon in the deer park at Sarnath made sense to him. John had also been to Dunhuang a few years previously and had been taken by a Chinese archaeologist into caves which most Chinese tourists did not see. Here he saw more designs of three hares, rabbits and deer.

“Some thought the Three Hares were of Mongolian or Central Asian origin, some Persian, but in the end nobody had the least idea at all.”

To John Crook “the symbol was very old and goes back to India itself to Benares where Buddha gave his first sermon. The symbol mirrors the diffusion of Buddhist teaching into Tibet, Mongolia and now England and Europe, which is why people are so interested. The teaching has come full circle. And it is a joke to see all these Christian churches in Devon having in their roofs symbols of the Buddhist teaching. Quite a joke…”

So then we met Tashi Rabgyas, the old Ladakhi philosopher, in Leh for lunch. He agreed with all of the above, and also said that the hare was a bodhisattva in the moon. And there are again many Tibetan folk tales about that. “When startled hares run a bit and then stand still, they are often upright and yet alert. An animal meditating.” So in Ladakh the fact that Three and Four Hares symbol is located in very ancient places in Alchi and Basgo is remarkable. In many ways the Three Hares symbolise compassion which is the underlying philosophy of Buddhism. For Tashi it went even further. It was a Madhyamika Hare. Even emptiness was empty.30

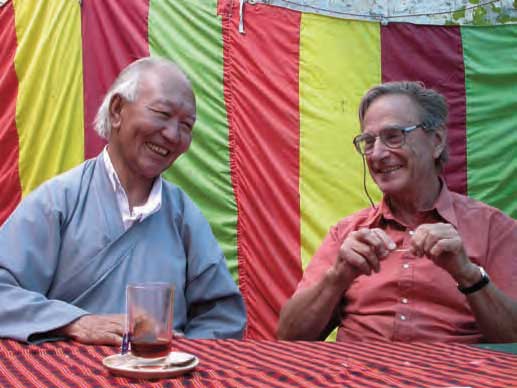

The philosopher Tashi Rabgyas and Dr John Crook discussing hares and bodhisattvas, Leh, Ladakh, Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir, 2004 Photo: Carol Trewin

So when you see a hare running round in a circle and then stopping to look at you as if it is meditating, the answer is that it is indeed a hare and the chances are it is a Tibetan woolly hare, and it is also a bodhisattva: Form and Emptiness. Quite a bit going on between the ears.